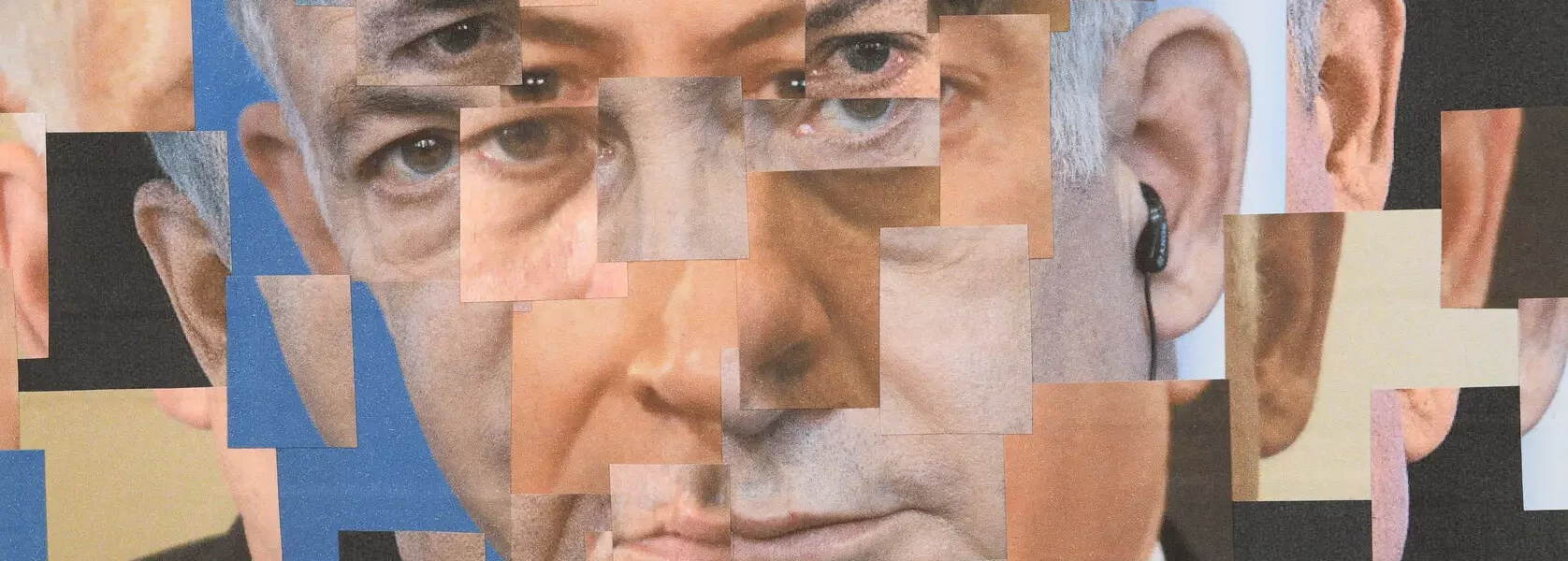

Flanked by two bickering ministers, Benjamin Netanyahu appeared to shrivel in his seat. It was late July in the Knesset, the last week before the summer recess, but there was no anticipatory buzz in the air. While lawmakers were preparing to vote, anti-government protesters, walled off from Parliament by newly installed barbed wire, chanted “Busha!” — “Shame!”

Sitting to Netanyahu’s left was Yariv Levin, Israel’s dour justice minister, a man “with less charisma than that of a napkin,” in the mordant opinion of Anshel Pfeffer, a Haaretz journalist and Netanyahu biographer. To Netanyahu’s right was Yoav Gallant, a former major general who serves as Israel’s defense minister. The two ministers hail from the right-wing Likud party, as does Netanyahu himself. But their consensus — much like every other consensus in the country — had splintered. Levin’s camp was bent on using the government’s majority to pass a package of bills that would do away with judicial oversight in the country and concentrate power in its hands. Gallant’s camp, seeing the extraordinary blowback that the bills had touched off around the nation, worried that this was a step too far.

The manner of the proposed legislative package (unilateral; rushed through) and scope (total overhaul of the system) had managed to rattle a public that had already accepted the most extremist coalition in Israeli history. Israel has no written constitution. Its Parliament is largely toothless as a check on power: The governing coalition has the majority and the means to impose its decisions there. Now it was proposing to neutralize the only curb to executive overreach: the country’s Supreme Court.

With the proposed judicial overhaul came ominous warnings from Moody’s and other financial agencies about a “deterioration of Israel’s governance” and a downgrading of the country’s credit outlook. Foreign investments were pulled; the shekel depreciated. Military reservists threatened to not show up for duty. Panicking, Netanyahu, Israel’s longest-serving prime minister, suspended the legislation in March. But this prompted his base to rebel, calling it a “surrender.” As one Likud lawmaker posted on Twitter, “You voted right and you got left.” The pressure on Netanyahu closed in from all sides. “If it were up to Bibi, the overhaul would simply disappear, but he can’t because the genie is now out of the bottle,” Tal Shalev, a political reporter for Walla News, told me.

By July, Netanyahu calculated that he was paying a steep public cost and getting nothing in return. Suspending the legislation had been a strategic mistake, his advisers reasoned: If the other side realized that the “unilateral threat is real” — that the government was willing to pass bills without seeking wider approval from the opposition — “they’ll move to compromise,” a source close to Netanyahu told me earlier that month. The judicial overhaul was back on the table.

The issue before Parliament now, as Netanyahu sat between his squabbling ministers, was an amendment that would bar the Supreme Court from using a standard of reasonableness to reverse government decisions. Gallant was desperate for a last-minute compromise, concerned about military disunity. Levin was steadfast in his intention to push the law through.

The judicial overhaul has now jeopardized every one of his perceived accomplishments, including Israel’s economic success and its international standing. Netanyahu is “in a Job-like state,” Nahum Barnea, a veteran columnist for Yedioth Ahronoth, told me. His coalition members embarrass him on a daily basis. His legal woes are mounting. On top of which, Barnea added, “He can’t travel to the White House, and it’s killing him.” (Netanyahu’s meeting with President Biden on Sept. 20 was the first since Netanyahu’s re-election last November and came on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly.) Still, many who know Netanyahu well rebuff the suggestion that he is losing control. “That’s like saying that Orban or Erdogan has lost control,” a former senior aide to Netanyahu told me recently.

But while the judicial overhaul is unpopular — only one in four Israelis wants it to proceed, according to a recent survey by the Israel Democracy Institute — it hasn’t diminished the passion of Netanyahu’s core supporters. In a recent poll measuring suitability to lead the country, he and Benny Gantz, who heads the centrist National Unity party, were tied with 38 percent each. (By comparison, Lapid, the current opposition leader, trailed them with 29 percent.) For vast parts of the country, from the Jewish settlements in the West Bank to ultra-Orthodox enclaves to Israel’s impoverished development towns, he remains “King Bibi.”

His status is such that his personal base of supporters is far greater than that of his party. Campaign posters from 2019 showed him shaking hands with Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, with the caption “Netanyahu: A Different League.” For his electorate, he is exactly that: a once-in-a-generation leader, suave and polished, speaking a refined American English, and also a bare-knuckled sabra who has shown no qualms about taking on Barack Obama, the Palestinian leadership and the U. N. Security Council. “He has turned himself into a symbol for entire sectors of the public that are drastically different from him but that are willing to die for him,” Zeev Elkin, a former Likud minister under Netanyahu who is now chairman of National Unity, told me.